We’re all familiar with Unicorns – private companies with valuations in excess of $1 billion, such as Stripe, Dischord, Coinbase, Robinhood, Instacart, and approximately 600 others. Deep pocketed tech investors flock for a piece of their technology-driven, game-changing upside potential.*

We’re all familiar with Unicorns – private companies with valuations in excess of $1 billion, such as Stripe, Dischord, Coinbase, Robinhood, Instacart, and approximately 600 others. Deep pocketed tech investors flock for a piece of their technology-driven, game-changing upside potential.*

Affiliations with entrepreneurial icons such as Elon Musk don’t hurt either, whether or not their rockets can land without, for instance, exploding.

Less well known are the small businesses whose profiles are to run of the mill commercial bankers what the Unicorns are to Silicon Valley venture capitalists.

Let’s call these businesses “Lolas.” Just wait for it.

Banks – especially local community and smallish regional banks – absolutely love to do business with Lolas. Your business may already fit that profile (or could with just a slight tweak to your business plan).

The key characteristic of a Lola is they are regular businesses that operate out of owner-occupied commercial real estate. The underlying business can be from virtually any industry.

Other than being its own landlord, the minimal requirements for Lola status are that the business be “established” (for purposes of this discussion let’s say at least two years of continuous operations) and profitable, without too much other debt.

Think of the local dentist or medical practice, a CPA or small law firm, a manufacturer in an industrial park, a CrossFit gym, or a local retailer. Even a restaurant can be a Lola.

This profile is especially attractive to banks because of how banks run their commercial loan portfolios. Typically, commercial loans are divided into two broad categories: Commercial Real Estate (CRE) and Commercial & Industrial (C&I) loans.

CRE loans are made to investors who function as third-party landlords and are collateralized by income-producing real estate. Classic examples are shopping centers and apartment buildings: rental income from tenants provide the ongoing cash flow to service the underlying loan.

With the hard-asset backstop of real estate providing additional security, these loans are relatively low risk. The downside is twofold: due to the perceived safety, these relationships tend to be less profitable, and eventually most banks, but especially small ones, become significantly over weighted in highly correlated commercial real estate, which can backfire in a big way.

C&I loans present the opposite dilemma: lots of revenue potential offset by higher perceived risks. A C&I relationship provides much more opportunity for a bank to increase deposits, and to sell additional products such as cash management and merchant services.

On the flip side, there are fewer hard assets to serve as a collateral fallback in a worst-case scenario.

And as we all know, when making a loan, the primary objective of a bank is to be repaid in full. Without a hard-collateral backstop, C&I loans are less attractive to the bank, and thus harder to obtain – especially from a local bank.

This is where Lola comes in.

How to put it? Lolas represent a little bit of both of these loan profiles. Underneath it all, a Lola is a C&I operating company, with all of its deposits and servicing needs. However, a Lola is also able to get dressed to the nines in real estate collateral.

And as a banker, let me tell you, this is far better than champagne that tastes just like Coca-Cola.

The Small Business Administration even has a loan program built specifically for Lolas. The SBA 504 program allows borrowers to leverage their owner-occupied commercial real estate up to 90% (vs. 70%-75% for a typical commercial loan), is especially protective of the bank’s collateral position, and features low, long-term fixed interest rates.

And the program can be used for commercial real estate purchases, making it especially attractive for aspiring Lolas and their love-struck bankers.

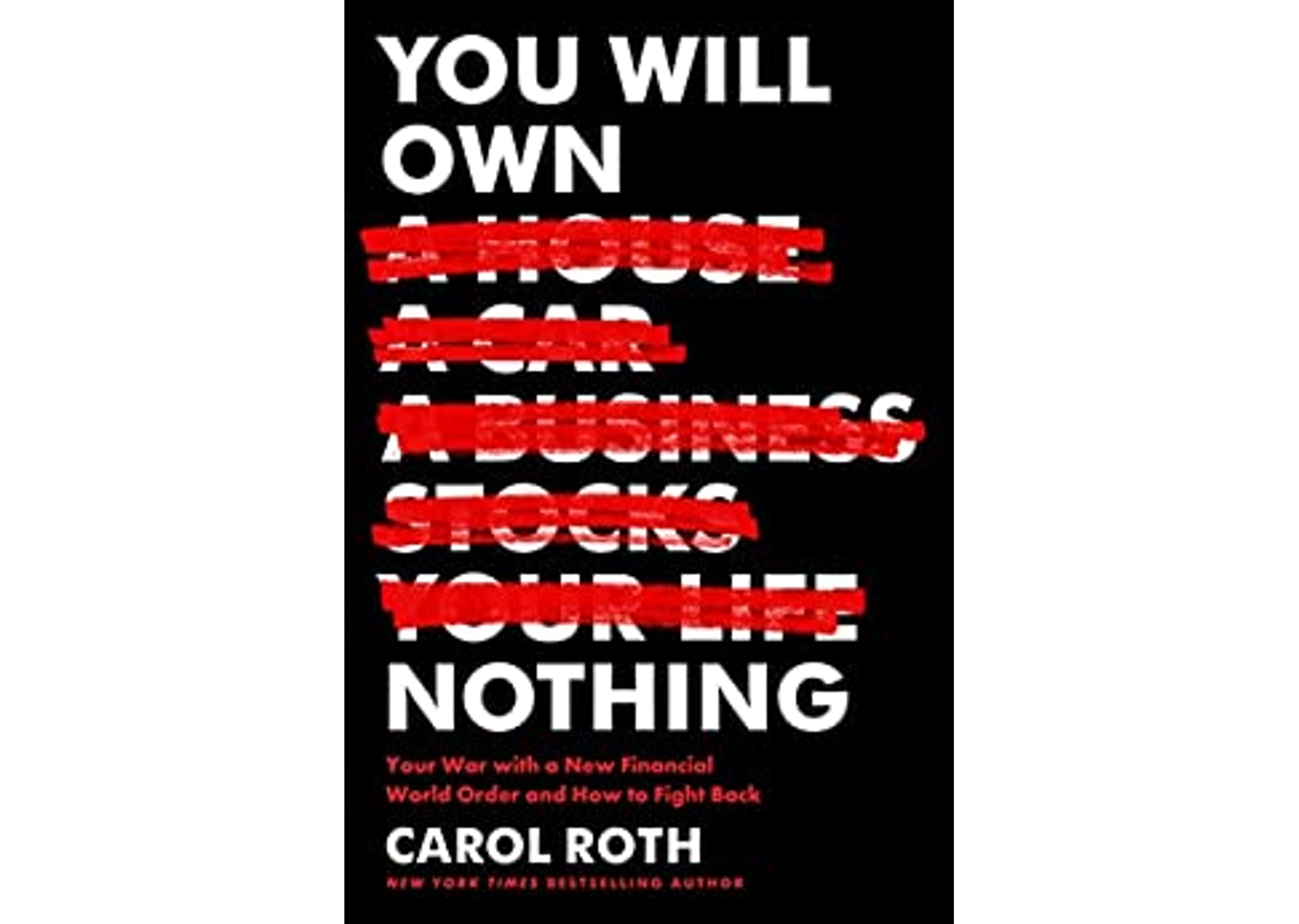

* The author’s opinions don’t necessarily reflect those of Carol Roth or Intercap Merchant Partners, LLC